Introduction

During my time as an assistant in Theoretical Electrical Engineering at Ruhr University Bochum in the 1970s, our optics lab smelled of film developer, vinegar, and occasionally cigarette smoke – which we used to make the “invisible” laser beams in our complex setups visible. Surrounded by heavy optical benches and vibrating pumps cooling our argon laser, we explored the many possibilities of holography.

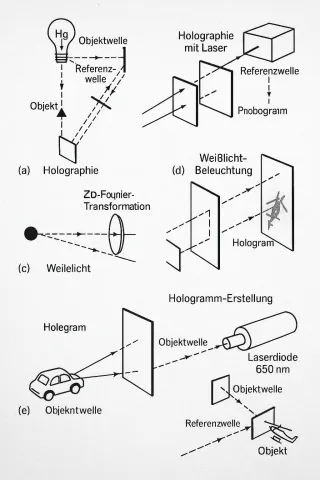

Its difference from photography is fundamental: a hologram records not only brightness and color but the light field itself – both amplitude and phase. When reconstructed, it produces a three-dimensional image in space – a frozen fragment of light.

The Idea: Dennis Gabor and the Frozen Wavefront

In 1947, Dennis Gabor formulated the concept of “wavefront reconstruction” – capturing the entire interference structure of a wave to later replay it optically. Lacking lasers, he used the minimal coherence length of mercury vapor lamps (green spectral line) to produce early transmission holograms. They were blurry and vibration-sensitive but proved the principle. With the invention of the laser in 1960, the method became stable; Gabor received the Nobel Prize in 1971.

The Breakthrough with Laser Light

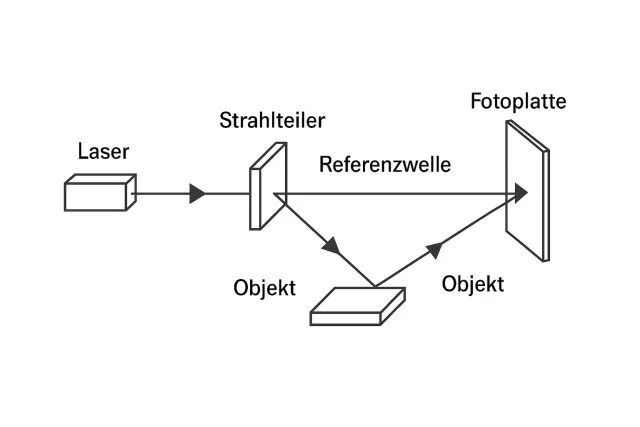

In the early 1960s, Emmett Leith and Jurijs Upatnieks achieved the decisive step: the off-axis hologram. A slight angle between the object and reference waves separated the interference orders cleanly – true 3D reconstructions became possible.

- Ruby laser (694 nm): first solid-state laser (Maiman), pulsed; historically significant but thermally unstable.

- He-Ne laser (632.8 nm): continuous-wave, stable, long coherence length – the workhorse of classical holography.

- Argon-ion laser (514 nm): bright, cooling-intensive, ideal for fine-grain color holograms.

- CO₂ laser (10.6 µm): infrared region; used in material and thermal interferometry.

- Laser diodes (650 nm): compact, inexpensive, sufficiently coherent – the foundation of modern digital holography.

Interference, Coherence – and the Lens as an “Optical Computer”

A hologram arises from the superposition of two waves: the object wave interferes with the reference wave on a recording medium. When the resulting interference pattern is illuminated correctly, a real or virtual 3D image appears.

Back then, we liked to ask students: “What is an optical computer?” – The answer: a convex lens. It performs a two-dimensional Fourier transformation at the speed of light: point source → plane wave → point. Pure elegance.

Experiments of My Own: White-Light and Rainbow Holograms

During my time in Bochum, I produced numerous holograms: classical transmissions, white-light reflection holograms, and rainbow holograms.

White-light reflection holograms: recorded under laser light, viewed with a point source (e.g. halogen lamp). The image floats freely in space – even without a laser. See White-Light Holograms with Argon Laser.

Rainbow holograms (Benton, 1968): vertical parallax reduced by a slit aperture during a second exposure – brilliant white-light holograms with characteristic color shifts when tilted. See Rainbow Holograms in Art.

Holography and Art

The connection between holography and art emerged early in Germany. Particularly in the Rhineland, exhibitions explored the medium as an aesthetic form – for example, at the Holography Museum Lauk in Pulheim and later in the Pulheim Town Hall Art Collection.

In the early 1980s, as I became editor of the magazine Ingenieur Digest (United Technical Publishers, later Elsevier), I wrote a major feature on laser technology. During that work, I recognized the artistic potential of holographic imaging and visited the Pulheim museum founded by Lauk – an experience that deeply impressed me. Among those light-sculpted objects, it became clear to me that in holography, the precision of physics and the intuition of art meet in a rare balance.

Speckle – The Grainy Memory of Light

What appeared as a poetic play of light in art became a precise measurement tool in science: holographic interferometry. Its refinement, speckle interferometry, exploits the fine-grained pattern that arises when laser light is scattered by microscopic surface irregularities. A surface need not appear rough to the eye – at optical wavelengths, nearly every surface is “rough enough.” The method works on metal, glass, plastic, or even paint and remains central to non-destructive material testing.

When a surface is illuminated by an expanded laser beam, a delicate pattern of bright and dark grains – the speckle pattern – emerges. It results from the interference of waves scattered at microscopic irregularities.

When one moves the head slightly, the speckles seem to drift in the opposite direction – a striking effect caused by changing phase relationships between eye and light field.

In speckle interferometry, this principle is used deliberately: recording an object twice – before and after a tiny deformation or shift – changes the speckle structure. Superimposing both images, e.g. on a screen, produces Young’s fringes, whose spacing and orientation directly reveal magnitude and direction of motion. Even displacements of a few hundred nanometers become visible.

Matched Optical Filters – Correlation at the Speed of Light

Beyond art and metrology, a third field opened: processing information in light itself. In Theoretical Electrical Engineering, we sought to perform mathematical operations such as correlation optically – fast, parallel, and without electronics. This led to the first matched filters operating, quite literally, at the speed of light.

Since classical optics cannot represent complex transmittances, these filters are realized as holograms (following Leith–Upatnieks), allowing the separation of the original and its complex-conjugate wave upon reconstruction.

In my research, I used fingerprints as test objects. Through optical correlation, the correct fingerprint was identified among many – as a bright light spot produced at the speed of light. Decades before digital pattern recognition, light itself was already performing computation.

I had originally planned to generate the first synthetic holograms on Ruhr University’s mainframe computer – a Telefunken TR440. The idea was to simulate interference patterns numerically and reconstruct them photographically. Since we still fed our code through punch cards, this would have been an ambitious and risky project. But the university was replacing the system with a Control Data Cyber, and beginning a six-month thesis during that transition seemed too uncertain. Thus, I climbed the mountain of holographic and speckle interferometry theory instead – though the idea of digital holography never quite left me.

A Broken Hologram – Whole Information

A striking example: my broken white-light hologram of a toy helicopter. The glass plate shattered – yet each fragment, properly illuminated, still displayed the full three-dimensional image.

Clarification: each fragment does not contain the entire object but the complete viewing angle of that point on the plate. Thus, the spatial image remains, albeit at reduced resolution – a key distinction in understanding holographic information.

Holography Today – From Silver Halide to Display

What once emerged on silver-halide plates in darkrooms is now captured by digital sensors and processed by computers. Holography has evolved from photographic technique to numerical science. Using modern Spatial Light Modulators (SLM), the full wavefront – amplitude and phase – can not only be recorded but also reconstructed and modified at will.

This makes Computer-Generated Holography (CGH) a reality: holograms are no longer recorded but computed. Numerical interference replaces the optical laboratory – the computer generates the patterns displayed on an SLM, LCD, or MEMS array, re-emitting light waves. This technology now underlies holographic displays where virtual objects seem to move freely in space.

Holography has also become a security feature on banknotes, passports, and credit cards. These color-shifting reflection holograms use the same principles as their analog predecessors but are embossed onto nanostructures – millions of identical, tamper-proof copies.

In research, digital holography enables phase-sensitive microscopy, tomographic 3D reconstruction, and even real-time observation of biological processes without contact. In quantum optics, it serves to generate and manipulate individual photon fields – a step toward controlled quantum information in space.

Holography has thus become a bridge between the analog world of waves and the digital world of algorithms and pixels. What once happened on vibrating optical tables now runs in computation clusters – yet the principle remains unchanged: the reconstruction of light itself.

Synthetic Holography – From Mainframe to Desktop

While modern holography controls light fields digitally, its principles can now be fully simulated – without lasers or plates. What required mainframes and punch cards in the 1970s can today be achieved on any laptop. The idea of generating interference numerically lies at the heart of Computer-Generated Holography (CGH).

With just a few lines of Python, one can compute and visualize the interference of object and reference waves – the ideal way to explore holography without a lab. Here is a simple example:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.fft import fft2, ifft2, fftshift

wavelength = 632.8e-9

pixel_size = 10e-6

z = 0.1

N = 1024

x = np.linspace(-N/2, N/2, N) * pixel_size

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, x)

obj = np.exp(-((X**2 + Y**2)/(0.0001**2)))

k = 2 * np.pi / wavelength

H = np.exp(1j * k / (2 * z) * (X**2 + Y**2))

hologram = np.angle(ifft2(fft2(obj) * fft2(H)))

plt.imshow(hologram, cmap='gray')

plt.title("Synthetic hologram (numerically computed)")

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

The result is a digital interference pattern representing a real hologram numerically. With slight changes, any image can replace the point source, producing virtual holograms. Displayed on a Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) or a high-resolution DLP projector, these patterns can even be optically reconstructed.

Thus, the circle closes: what was visionary on the Telefunken TR440 and later the Control Data Cyber can now be done on a laptop in seconds. Synthetic holography unites mathematics, optics, and creativity – a perfect field for curious minds, in the lab or at the desk.

Holography to Touch – Experiments with Laser Diodes

Back then, we worked with water-cooled argon-ion lasers on heavy optical benches, surrounded by lenses, beam splitters, and vibration-isolated tables resting on N₂-supported air bearings – an effort that made private experiments virtually impossible. Today, thanks to compact laser diodes and highly sensitive recording materials, the principle of holography can be explored even on a modest budget. With patience, darkness, and a steady hand, even students in “Youth Research” projects or school labs can produce impressive reflection or transmission holograms – experiments that inspire both curiosity and awe.

Recommended Components (Beginner Setup)

- Laser diode: 650 nm (< 5 mW), Class 2/3R (pointer type).

- Photographic plates: silver-halide (e.g. PFG-03M, Ultimate 08) – ≈ 3000 lp/mm.

- Setup: two-beam geometry (glass plate as beam splitter); object and reference meet at a small angle (~10–20°) on the plate.

- Mechanics: massive table or granite slab on foam; avoid drafts; expose at night.

- Development: chemical kit (e.g. JD-4/GP-2): develop → short rinse → bleach → final rinse → dry.

Procedure (Summary)

- Stabilize: warm up the laser and let the room settle.

- Alignment: adjust reference and object beams precisely onto the plate.

- Exposure: 5–10 seconds at ~5 mW.

- Development: follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Reconstruction: for reflection holograms, illuminate under the same angle as during exposure.

Budget: around €80–150 for a first setup; the result – a white-light visible reflection hologram – is surprisingly impressive.

Safety & Notes

- Never direct laser beams toward the eyes.

- Vibrations are the enemy of success.

- Avoid temperature and air fluctuations.

- Above 5 mW: use protective goggles; handle chemicals carefully.

And as we used to say in the lab: “Always add acid to water – never the other way around.”

Conclusion: The Memory of Light

A hologram is not an image of things, but a trace of their relationship with light. Even fragments preserve the full perspective – just as every part of a thought holds the entire idea within it. Between Gabor’s wavefronts, the Fourier lenses of my assistant years, and today’s digitally computed SLM displays, technology has evolved – yet the sense of wonder endures: light shows us how thought can take shape when we give it space.